ChatGPT has transformed scientific writing more rapidly than any event in recent history, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

This post examines a study quantifying ChatGPT’s impact on academic publishing by analyzing millions of research abstracts. It turns out that a huge percentage of new research papers contains telltale signs of AI-assisted writing. Let’s take a look at the study in question and see how the researchers quantified this phenomenon and what it might mean for the future of science!

By the way, I only heard about this paper because AImodels.fyi’s listening algorithm put it at the top of my dashboard. If you want to skip the noise and get short summaries of the research and models that really matter (like this), then sign up now!

This paper (“Delving into ChatGPT usage in academic writing through excess vocabulary”) introduces a method to detect AI-assisted writing in scientific publications. By examining word usage across over 14 million biomedical abstracts, the researchers found evidence of widespread ChatGPT, uh, adoption.

Their approach analyzes published papers directly, avoiding the limitations of previous studies that relied on synthetic AI-generated text. This allowed them to compare ChatGPT’s impact to other major events that influenced scientific writing in the past decade.

The paper covers their methodology for detecting “excess words”, ChatGPT’s overall impact, and usage patterns across fields, countries, and journals.

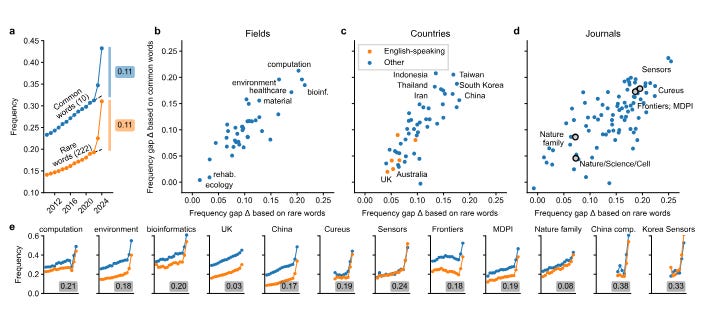

The researchers examined millions of scientific abstracts, looking at how often different words were used each year from 2010 to 2024.

After ChatGPT launched in late 2022, they noticed researchers using certain words and phrases much more often. Words like “delves,” “pivotal,” and “intricate” became far more common.

This word shift was larger than any other change in scientific writing over the past decade – even larger than how COVID-19 changed what scientists wrote about.

By counting these “excess words,” they estimate at least 10% of new research papers in 2024 were written with AI help. In some fields, it might be as high as 30%.

This method provides a way to track AI’s influence on science communication over time, which I think raises some questions about how it might shape future research.

The study introduces “excess word usage” to quantify LLM’s impact on scientific writing. Their methodology involved analyzing 14,448,711 English-language abstracts from PubMed (2010-2024). They preprocessed the data by cleaning abstracts of non-content text and computing a binary word occurrence matrix.

For excess word identification, they calculated each word’s frequency in 2024 (p), expected 2024 frequency based on 2021-2022 trend (q), excess frequency gap (δ = p – q), and excess frequency ratio (r = p / q). They used these metrics to determine which words were considered “excess.” They applied this analysis to 2013-2023 to contextualize changes and examined excess word usage across fields, countries, and journals.

Key findings revealed 382 excess words in 2024, compared to 189 maximum during COVID-19. The 2024 excess words were primarily style-related verbs and adjectives, unlike previous content-driven shifts. They estimated a lower bound of at least 11% of 2024 PubMed abstracts likely used LLMs, based on two word groups: 222 rare words (Δrare = 0.111) and 10 common words (Δcommon = 0.110).

Usage estimates varied across different categories. In fields, computational areas showed up to 20% usage. Among countries, some English-speaking nations had 3-4% usage, while China, South Korea, and Taiwan showed >15%. Journal-wise, Sensors had 24% estimated usage, while Nature/Science/Cell ranged from 6-8%. The highest subgroup estimates reached 33-38% for specific intersections, such as computational papers from China.

I think this study has several limitations and areas for further investigation. The 11% estimate is likely conservative, and true LLM usage may be higher. The study doesn’t prove direct causation between ChatGPT release and word usage changes. The analysis only examines abstracts, and full paper text may show different patterns.

The study is limited to English-language abstracts, potentially missing trends in other languages. Categorizing fields by journal names may oversimplify interdisciplinary research. Varying publication timelines across fields might also affect LLM usage detection.

But overall I think the study does raise questions about LLM use in scientific writing, thought without a super-deep exploration of implications. I guess some “excess words” might also reflect changing writing styles unrelated to LLMs. Cross-country differences could reflect varying abilities to “disguise” LLM text, not actual usage rates. Lastly, the study provides a point-in-time snapshot, and longer-term analysis is needed to understand evolving patterns (although the patterns look pretty stark based on the data presented).

This study shows AI writing assistants are changing scientific communication. The scale of the shift demands attention from the scientific community.

After reading this study, I think we should think about a few things:

-

How will widespread AI use will affect scientific discourse quality and novelty?

-

What are the benefits of LLM-assisted research writing? Do they outweigh the drawbacks?

-

What policies should govern AI-assisted writing in academia – should it really be fully banned? Can the toothpaste be put back in the tube here?

-

How we can balance AI writing tool benefits with homogenization or factual error risks?

This paper’s methodology offers a way to track AI’s influence on academic writing over time, which is cool. Monitoring these trends might be crucial for scientific integrity and innovation. I’d love to see how this trend compares to SEO content on Google – I expect it’s used for the majority of writing there.

What’s your view on AI in scientific writing? Share your thoughts in the comments. In the words of Company Man, I’d love to hear what you have to say. You can also comment on the paper on AImodels.fyi.

Source link

lol