This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

At the time of this writing, Southern California is battling one of its worst wildfire outbreaks in modern history—24 lives have been lost, 60 square miles have been burned, and more than 12,300 structures have been destroyed, including many residential homes.

Containing these fires (establishing barriers designed to prevent their spread) has been particularly challenging due to the strong Santa Ana winds blowing through the area, but firefighters are making progress—all but two of the large fires are now fully contained, and those, the Palisades and Eaton fires, are trending in the right direction (27% and 55%, respectively, at the time of writing).

Technology has been vital to this progress.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) is using a fleet of more than 60 aircraft to monitor and dump water and fire retardants on and near the fires. NASA satellites are tracking them from Earth’s orbit, providing updates to officials in near-real time, while the University of California San Diego’s ALERTCalifornia is collecting valuable data on the fires from cameras and sensors at ground level.

Tech has also been helping residents cope with the fires. Locals without internet access have been able to get online using SpaceX’s Starlink satellite network, and thousands of Californians are using wildfire-tracking app Watch Duty to access the latest information on the fires, including updates on their evacuation orders.

To find out how we got from bucket brigades to this tech-heavy approach to fighting fires, let’s explore the evolution of wildfire fighting tools in the U.S. and hear from the startup using aerospace-inspired technologies to help homeowners avoid losing it all if a wildfire does sweep through their neighborhood.

(Information on how you can help with wildfire relief efforts can be found here.)

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

While wildfires are common in California, the current blazes are proving to be among the state’s most destructive—weather forecaster AccuWeather is predicting they could cause $275 billion in damage before the situation is resolved.

“It may become the worst wildfire in modern California history based on the number of structures burned and economic loss,” Jonathan Porter, AccuWeather’s chief meteorologist, told AP News.

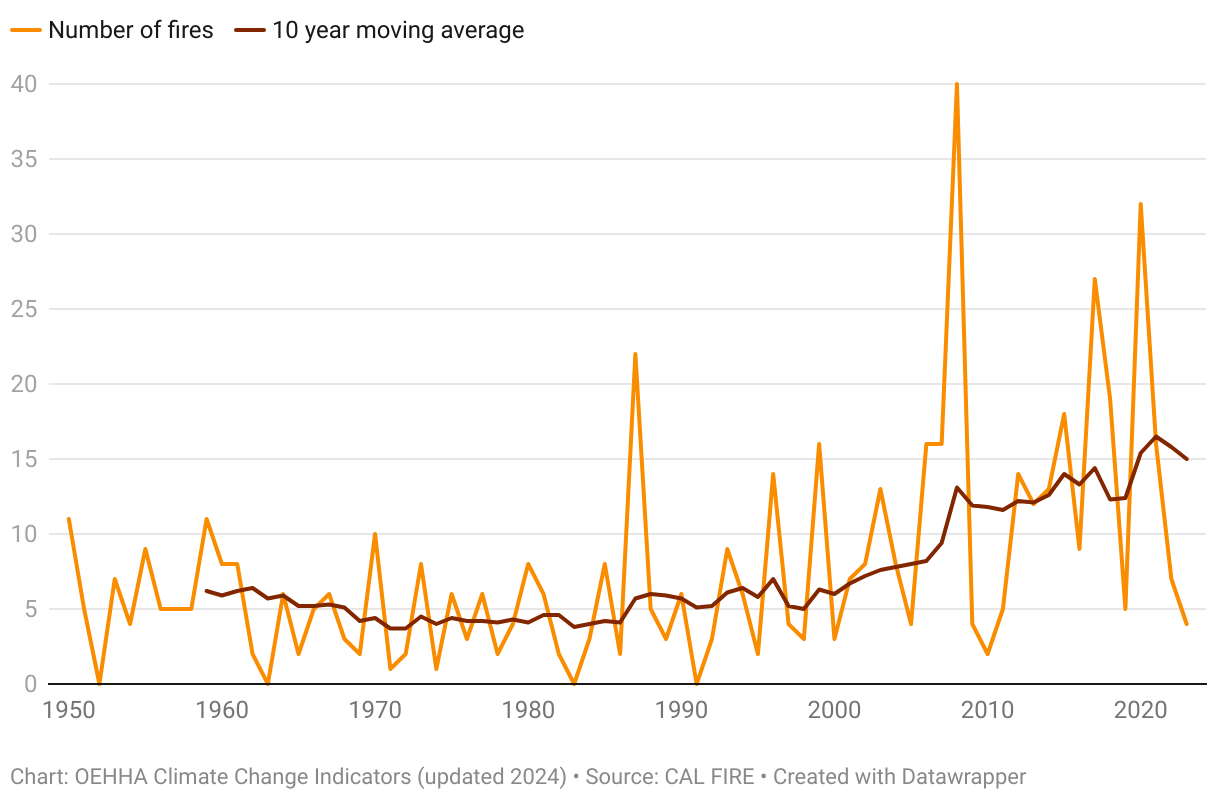

Though devastating, this destruction wasn’t entirely unexpected, as California has been experiencing more and more large wildfires recently. In the 1990s, the state averaged six per year, but in the 2010s, it was up to 12.2. (Depending on who you ask, this increase is due to climate change, forest mismanagement, more people living on the forest border, or some combination of these factors).

This trend hasn’t gone unnoticed by home insurers.

The companies rely on historical data—like an area’s wildfire patterns—to predict the likelihood that they’ll have to pay out a policy. If the likelihood is high, premiums are high. If it’s really high, though, they might decide insuring a home isn’t worth the risk and will decline to offer any coverage.

Thousands of Californians know this firsthand. Over the past five years, several major insurers have decided to drop coverage for residents living in areas with high wildfire risk, meaning some of those who’ve lost their houses in the 2025 fires are going to face a major economic hardship rebuilding.

“How can you produce a price for somebody based on a history that doesn’t exist?”

Dan Preston

San Francisco-based startup Stand Insurance believes the worsening effects of climate change have made it so that historical data is no longer the accurate predictor of future incidents that it once was.

“The last 10 years of data that we have about wildfire risk or flood risk or wind risk is telling us very little about the next 10 years because it’s changing very rapidly,” Dan Preston, the company’s co-founder and CEO, told Freethink.

“You have places that had never experienced 100-mile-per-hour winds leading to a cascading fire that can take out entire large neighborhoods,” he continues. “There’s no historical evidence of these things happening, so how can you produce a price for somebody based on a history that doesn’t exist?”

The answer, according to Stand, is to focus on the future.

An example of a “digital twin” created by Stand.

When someone reaches out to the startup about insurance, its first step is to create a detailed “digital twin” of their home and land—typically, this can be accomplished using existing data, but when necessary, Stand will use drones and site walks to collect extra information.

It then uses the same kinds of computer simulations used in aerospace engineering to model how a wildfire would behave as it crosses over the parcel of land. It can then change the digital twin in ways expected to increase the home’s fire resilience and rerun the simulations.

“We’ve been able to bring to bear these physics models that allow us to understand what the true impact would be given the physics of the home and the parcel outside of it,” Preston told Freethink.

“It allows us to simulate on a forward-looking basis what would happen given certain changes you would make to the property,” he says. “We can say the home can survive up to X-mile-per-hour winds in wildfire conditions or wherever it might be.”

Armed with that data, Stand can then give the homeowner a list of recommended changes to make to the property, along with a quote for what the insurance premiums would be if those changes were made.

Stand isn’t just recommending that everyone turn their house into a concrete bunker, either. It talks with prospective clients to figure out what they love about their homes (e.g., a favorite tree, a vegetable garden, etc.) and considers those characteristics when doing its modeling.

“In most cases, we can protect the most important stuff and still propose changes that will make it resilient,” says Preston. “For the most part, it’s clearing out some vegetation or making some minor changes to decking or siding. It’s typically a fraction of the insurance policy and cost.”

“It’s much better to have expensive insurance than no insurance.”

Mark Mitchell

Stand has already started issuing insurance policies to California residents, and they aren’t cheap—Preston told the Wall Street Journal that coverage for a $3 million home in a region at high risk of wildfires could cost $12,000 to $15,000 in annual premiums.

For people who’ve been abandoned by traditional insurers, though, the cost is worth the peace of mind.

“For us, it’s much better to have expensive insurance than no insurance,” Mark Mitchell, Stand’s first customer, told the Journal. “They are the only company that has been able to figure out how much we’ve done to protect our house and that it’s a reasonable risk to insure.”

Stand won’t know for sure that the risks it’s taking are reasonable until some time passes, though. If too many of the homes it agrees to cover are damaged by wildfires, payouts could exceed income from premiums, and the startup won’t be able to turn a profit (it came out of stealth in December 2024 with $30 million in funding from Inspired Capital, Lowercarbon, Equal Ventures, and Convective Capital).

Preston is confident in his team’s technology, however.

“The way that we can trust these models is that they are not just statistical simulations. They are true, almost deterministic models,” he says. “It’s actually computing a set of physical equations that determine what happens next.”

“That said, you have to make some assumptions within those, but there is a bunch of good research and empirical data that you can get,” he adds, noting how the company was able to incorporate research on the thermal loads of different tree species into its models.

“I think there’s an exciting world where we could design a neighborhood through the same methodology used for individual homes.”

Dan Preston

For now, Stand’s goal is to issue policies worth a total of $2 billion in coverage before the end of 2025, and it’s targeting homes worth $2 million to $10 million only for two reasons.

One is the California FAIR Plan. It was established by California to provide up to $3 million in fire coverage for residents who can’t get it elsewhere, and according to Preston, competing with a state-subsidized insurance plan for this market would be tough.

The other reason is that homes valued lower than $2 million generally aren’t capable of making the changes needed to increase their fire resilience, often because they’re closer to their neighbors than more expensive homes.

“The most likely vulnerability for a home is the distance to its neighboring home, which we saw in the Pacific Palisades fires,” says Preston.

“If we’re selling to a single homeowner, they need to be able to make changes to their parcel that will impact the fire risk enough, and it’s typically in these higher ranges where they can do that,” he explains.

Once Stand demonstrates that its approach works with homes in this range, it could start to insure homes outside of it, but Preston says the longterm goal is not only to help more individuals protect their homes from wildfires, but also to help entire neighborhoods, perhaps by licensing its technology to city officials.

“I think there’s an exciting world where we could design a neighborhood through the same methodology used for individual homes and make that whole neighborhood resilient with a set of changes—some homeowners change some things, the town does some smaller things—then you don’t have this kind of cascading fire issue,” he told Freethink.

“That’s how I think, ultimately, you make a much bigger impact because now you can make whole neighborhoods and cities much safer.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].

Source link

lol