Paul and Joshua, two of Deephaven’s college interns, published their first blog yesterday. It foreshadowed a summer journey to dig deep into the MLB Fantasy game, Beat the Streak. I’m a baseball fan, so it’s a project that naturally attracts my interest.

The original goal of their project was to use Python on static data, then replayed sets, then real-time pitch-by-pitch streams – doing analytics, building applications, supporting user experiences. Progressions like that are natural for Deephaven users.

A few days into the project, though, they’ve found their north star.

We need to identify MLB players that have a 76% chance of getting a hit in the next game.

That’s it.

These interns really want this game to be beaten and believe it can happen. By someone. Propagating shared quantitative models and encouraging more players might make it so. In support of such ambitions, there is a significant breadth of new, high-density data that seems under-utilized in forecasting hitting percentages.

It’s an exciting pursuit for college interns. A big idea. Deephaven is on board.

With Paul and Joshua at the lead, we want to invigorate MLB leadership, MLB hitters, baseball enthusiasts, and sports fans everywhere to try to collectively Beat the Streak. Yes, only one person will actually win the $5.6 million, but beating Joe DiMaggio would be a colossal feat, even if a shared one.

Beating Joe’s streak is like being on the winning team of the Tour de France. You may not get the yellow jersey, but being part of the peloton that catapults a record-breaker is its own version of awesome.

Maybe this is a better analogy. From 2016 to 2019, Nike organized an attempt to unseat a record. “Breaking2” was a manufactured event that helped Eliud Kipchoge break the 2-hour mark in the marathon. Although it was staged, it was still exciting. The key to winning? Rotating teams of pacers that both helped him maintain speed and ran in a formation to slightly reduce drag. Those pacers got no glory, but they were on the team when something amazing happened.

In terms of that analogy, Beating the Streak might need a million pacers.

Simply stated, Joe had something special going on. Below is a graph of his hits per game in 1940 and 1941, per retrosheet’s raw data. (The gap between 132 and 147 is an artificial space separating the two years.) One thing should pop off the page: Joe got hits in a lot of games. Period.

Joltin’ Joe got a lot of hits per game.

Before his streak, here are his numbers from 1940 and early 1941:

- 157 game starts

- 737 plate appearances (“PA”)

- 4.69 PA / game

- 224 Hits

- 0.304 plate appearance average (“PAA”), which is not the same as batting average

- 129 Games with a Hit (“GWH”)

- 0.822 Games with a Hit Percentage (“GWH%”)

Again, this is before the streak!

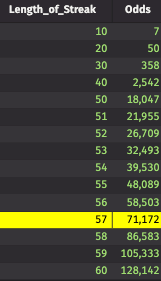

The streak odds if there was a hypothetical pool of players, each with 0.822 GWH%.

A 1-in-71,000 chance at $5.6 million would be a pretty sweet deal.

It’d be silly for me to guess why Joe’s numbers (before the streak) are so off-the-charts by today’s standards. He got 4.7 plate appearances per game – a huge number… rarely struck out… and seemingly didn’t like to walk. He’s a legend, pitching has evolved, the game has changed. Those broad strokes encapsulate the story.

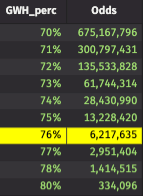

Let’s start with a baseline grounded in today’s game. Reading Paul’s introductory post, it seems like picking a player with a 72% GWH% is pretty achievable. One can target a player that should get 4 at-bats and have a PAA of 0.273. Top MLB players achieve at that level.

But we need to do better than 72%. We need to get to 76%.

If 76% is the goal, there are two implications to the quest:

-

Can quantitative modelers use newly available data to identify players that have a 76% chance of getting a hit in the next game?

-

Are there actually enough MLB players on any given day that have that magnitude of predicted-GWH%, so that the law of large numbers can help Streakers, collectively, get to the 57-games-in-a-row mark? Said another way, the Streaker community needs to diversify its daily bets – will there be enough compelling hitters to bet on?

Research is always risky, but it’ll be worthwhile to watch the interns give it a go. Hopefully, researchers that have worked on this before, like Ryan McKenna, Matthew McNew, Ilan Goodman, or Elena Frey, will weigh in and provide counsel.

Ultimately we expect that Statcast data will be helpful. As any baseball player knows, good at-bats are the real predictor of future results, and successfully getting hits over the last many dozens of games is a very coarse and wobbly metric for such efforts. Statcast has detailed data about historical swing activity, contact, and ball flight that may provide helpful signals.

Spending legitimate energy to try to win Beat the Streak yourself is an exercise in futility. Whether your chances are similar to the real-world odds of 1-in-200,000,000 or (magically, hypothetically) 1-in-20,000, you’re incredibly unlikely to win on your own. Even over a 50-year (fantasy) playing career.

However, playing alongside others – particularly with a shared model, social experiences to see how “the team” is progressing, and quick interfaces to watch the MLB at-bats themselves – would be fun. And that’s the point, right?

The progress on research and signal-farming on historical data will be worth watching, but I’m looking forward to the interns moving toward real-time experiences and feedback. Whenever I’ve watched the NFL and AWS “Stat That” ads, I’ve always thought, “I wish you could see stuff like that in real time.”

A fantasy game we play collectively, while monitoring MLB stars pound out hits in real time, could present a new wave of live sports engagement.

Particularly when Byron Buxton breaks The Streak.

Source link

lol